Hard-boiling, soft-boiling or a trendy sous vide—no matter the approach, cooking a whole egg attains ideal texture for either the yolk or the white but rarely both. Now, however, scientists think they have cracked the perfectly cooked egg.

To trigger the optimal denaturation, or breakdown, of proteins while also keeping key nutrients intact, the ideal temperature for cooking an egg yolk is around 149 degrees Fahrenheit (65 degrees Celsius). For the egg white, or albumen, it’s around 185 degrees F. Hard-boiling ensures the albumen is fully cooked, but it can yield a chalkier yolk. Soft-boiled eggs have a smoother yolk that can be too runny for some people’s taste. A sous vide egg—cooked in water at 140 to 158 degrees F for at least an hour—is close to the ideal. The resulting egg is creamy all the way through, but the albumen is only partially set. The necessary appliance is also not a common kitchen feature.

Materials science postdoctoral researcher Emilia Di Lorenzo and professor Ernesto Di Maio, both at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy, typically work on methods for making polymers with layers of different densities. But for a recent study in Communications Engineering, they sought a novel method for preparing an egg that would allow the yolk and egg white to cook optimally without being separated. “What we did in the case of eggs was to take this approach and try to get a layer of texture instead of a layer of densities,” Di Lorenzo says. Their inspiration was an €80 (about $87) egg dish in which the components cooked perfectly but separately.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Di Maio theorized that alternating an egg, still in its shell, between hot water and tepid water repeatedly for short periods would allow both yolk and albumen to reach their perfect form. The researchers used mathematical modeling and computer simulations to establish their alternating temperatures (212 and 86 degrees F), times (32 minutes total) and cycles (switching every two minutes). Then they cooked a lot of eggs to test their new method.

The team examined its results with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, which uses infrared waves to probe chemical structure, to find out how protein breakdown in the egg yolk and white had affected the texture of eggs that were hard-boiled, soft-boiled, cooked via sous vide or prepared with the new method.

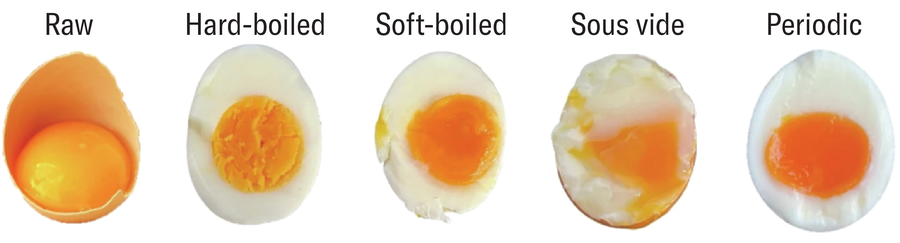

The texture of an egg yolk and white when it is raw, hard-boiled, soft-boiled, cooked by sous vide, and cooked with the new "periodic" method.

“Periodic Cooking of Eggs,” by Emilia Di Lorenzo et al., in Communications Engineering, Vol. 4, Article No. 5. Published online February 6, 2025

Of course, when you are making eggs at home, you’re probably not ranking your preparation options based directly on the degree of protein denaturation—so the researchers further probed the overall texture and taste of the eggs with the help of some experts.

Texture profile analysis, which involves compressing pieces of egg, revealed that the hard-boiled egg’s albumen and yolk were harder and chewier than the other options but that the rest of the preparations were only subtly different. A panel of sensory experts assessed the eggs’ more subjective taste differences.

In the end, the team went through dozens upon dozens of eggs. There were “160 alone for the sensory analysis—personally cooked by Di Maio” in his kitchen, Di Lorenzo says.

The researchers found that if you’re looking to maximize your morning nutrition, their newly proposed “periodic” cooked egg may be the way to go. Nutrients were better preserved in the periodic eggs than in other preparations. “The most outstanding result was the preservation of polyphenols, but a lot of amino acids are preserved as well,” Di Lorenzo says. Amino acids are useful for building proteins in our body, and polyphenols are antioxidants that show promise as anti-inflammatory compounds.

The project changed Di Maio’s egg routines forever. Although he acknowledges that the preparation takes a bit longer than common kitchen methods, he’ll be periodic cooking going forward. Di Lorenzo, however, may not change her diet.

“We were really already deep into this egg project,” Di Maio says, when Di Lorenzo “told me that she doesn’t like eggs—at all.” But cracks are appearing in Di Lorenzo’s attitude. “Maybe,” she proposes, “this was a quest to try to like eggs.”